In my continuing reclamation of lost heritage (see An Introspection of My Identity), I’ve been giving sustained thought to language—specifically, the language I would have learned by lineage rather than by conquest.

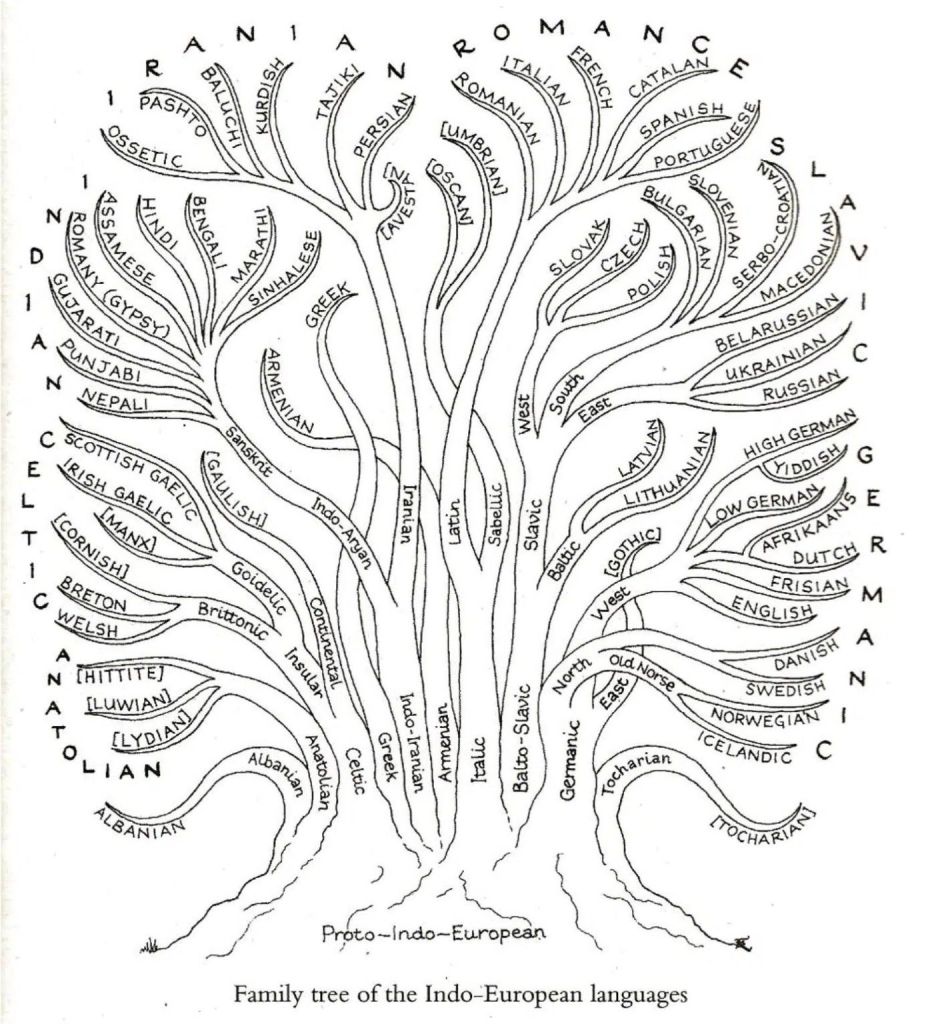

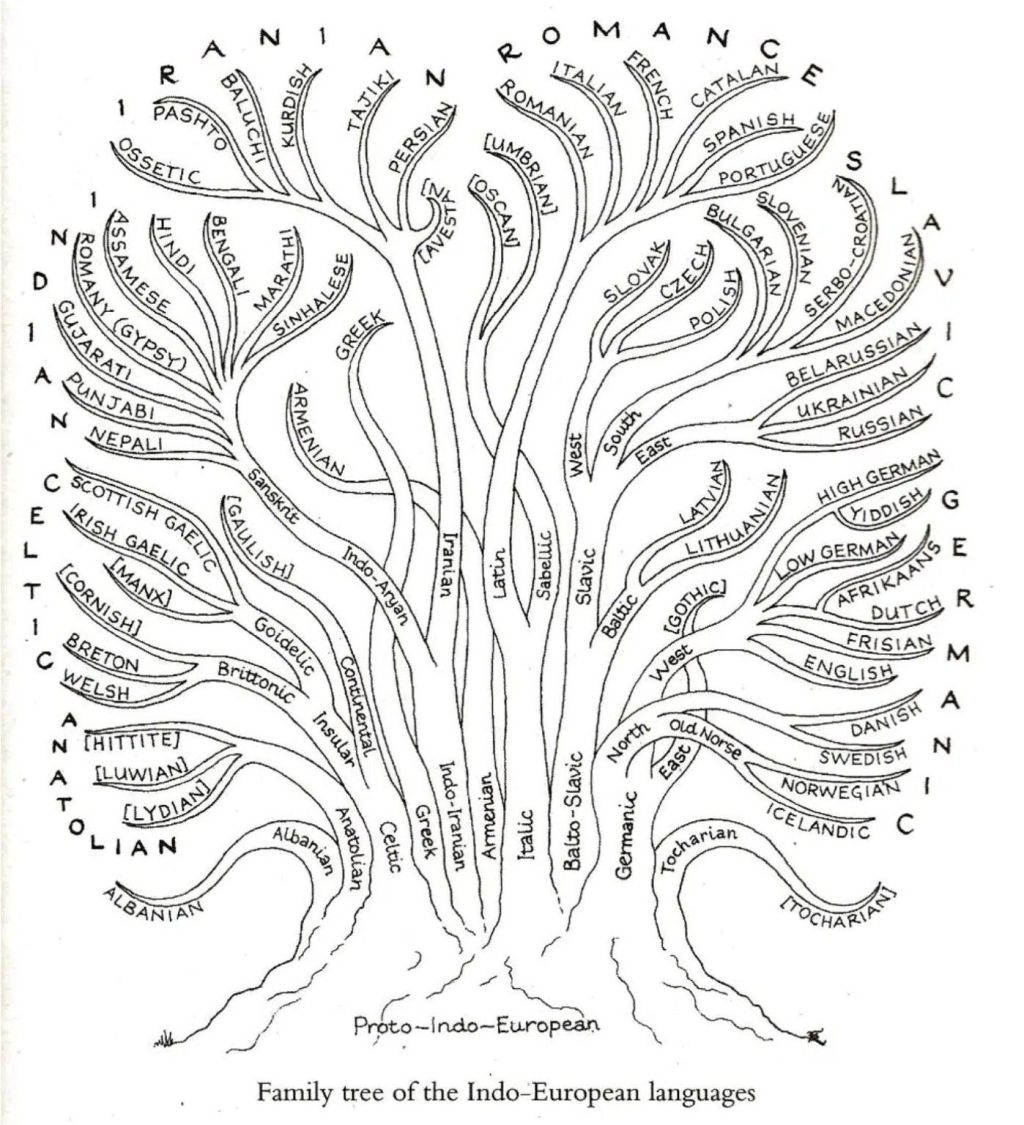

The English I speak today is Germanic in structure and imperial in history, shaped and imposed through centuries of Christian and political domination. It is not the language that would have arisen naturally from my ancestral line. By geography and history, the native tongue of my forebears would have been Celtic in origin—older than Cornish itself. But as that earlier language no longer survives, Cornish stands as the closest living descendant, and so it is the language I have chosen to learn.

More than a personal act of study, this choice has grown into a broader proposition: Cornish as the aspirational native language of the Utopian Society.

This is not nostalgia, nor ethnic romanticism. It is design.

By adopting a revived Celtic language as its civic and ceremonial tongue, the Utopian Society makes a deliberate break from imperial inheritance. Cornish belongs to no modern empire, no global power, no economic bloc. It carries no geopolitical authority, no administrative violence, no history of expansion by force. It is, by circumstance, neutral.

In this way, the language becomes an act of symbolic repair—for cultures suppressed, overwritten, or erased by conquest. It offers a lingua franca not because it is dominant, but precisely because it is not. It would be a language learned intentionally, by consent, rather than absorbed through coercion or birthright.

Historically, empires spread languages by force—through law, religion, education, and punishment. Language became a tool of obedience, administration, and erasure.

I am proposing the inverse.

A language adopted freely.

A language carried forward because it was chosen.

A language that serves memory rather than power.

This is not about rejecting English, but about refusing to let conquest have the final word. Language, like culture, can be repaired—not by undoing history, but by choosing differently going forward.

Reparation, in this sense, is not retroactive guilt. It is prospective responsibility.

And it begins with the words we decide to speak.

Leave a comment